Introduction

Groovy…

-

is an agile and dynamic language for the Java Virtual Machine

-

builds upon the strengths of Java but has additional power features inspired by languages like Python, Ruby and Smalltalk

-

makes modern programming features available to Java developers with almost-zero learning curve

-

provides the ability to statically type check and statically compile your code for robustness and performance

-

supports Domain-Specific Languages and other compact syntax so your code becomes easy to read and maintain

-

makes writing shell and build scripts easy with its powerful processing primitives, OO abilities and an Ant DSL

-

increases developer productivity by reducing scaffolding code when developing web, GUI, database or console applications

-

simplifies testing by supporting unit testing and mocking out-of-the-box

-

seamlessly integrates with all existing Java classes and libraries

-

compiles straight to Java bytecode so you can use it anywhere you can use Java

1. Groovy Language Specification

1.1. Syntax

This chapter covers the syntax of the Groovy programming language. The grammar of the language derives from the Java grammar, but enhances it with specific constructs for Groovy, and allows certain simplifications.

1.1.1. Comments

Single line comment

Single line comments start with // and can be found at any position in the line.

The characters following //, till the end of the line, are considered part of the comment.

// a standalone single line comment

println "hello" // a comment till the end of the lineMultiline comment

A multiline comment starts with /* and can be found at any position in the line.

The characters following /* will be considered part of the comment, including new line characters,

up to the first */ closing the comment.

Multiline comments can thus be put at the end of a statement, or even inside a statement.

/* a standalone multiline comment

spanning two lines */

println "hello" /* a multiline comment starting

at the end of a statement */

println 1 /* one */ + 2 /* two */GroovyDoc comment

Similarly to multiline comments, GroovyDoc comments are multiline, but start with /** and end with */.

Lines following the first GroovyDoc comment line can optionally start with a star *.

Those comments are associated with:

-

type definitions (classes, interfaces, enums, annotations),

-

fields and properties definitions

-

methods definitions

Although the compiler will not complain about GroovyDoc comments not being associated with the above language elements, you should prepend those constructs with the comment right before it.

/**

* A Class description

*/

class Person {

/** the name of the person */

String name

/**

* Creates a greeting method for a certain person.

*

* @param otherPerson the person to greet

* @return a greeting message

*/

String greet(String otherPerson) {

"Hello ${otherPerson}"

}

}GroovyDoc follows the same conventions as Java’s own JavaDoc. So you’ll be able to use the same tags as with JavaDoc.

Shebang line

Beside the single line comment, there is a special line comment, often called the shebang line understood by UNIX systems

which allows scripts to be run directly from the command-line, provided you have installed the Groovy distribution

and the groovy command is available on the PATH.

#!/usr/bin/env groovy

println "Hello from the shebang line"

The # character must be the first character of the file. Any indentation would yield a compilation error.

|

1.1.2. Keywords

The following list represents all the keywords of the Groovy language:

as |

assert |

break |

case |

catch |

class |

const |

continue |

def |

default |

do |

else |

enum |

extends |

false |

finally |

for |

goto |

if |

implements |

import |

in |

instanceof |

interface |

new |

null |

package |

return |

super |

switch |

this |

throw |

throws |

trait |

true |

try |

while |

1.1.3. Identifiers

Normal identifiers

Identifiers start with a letter, a dollar or an underscore. They cannot start with a number.

A letter can be in the following ranges:

-

'a' to 'z' (lowercase ascii letter)

-

'A' to 'Z' (uppercase ascii letter)

-

'\u00C0' to '\u00D6'

-

'\u00D8' to '\u00F6'

-

'\u00F8' to '\u00FF'

-

'\u0100' to '\uFFFE'

Then following characters can contain letters and numbers.

Here are a few examples of valid identifiers (here, variable names):

def name

def item3

def with_underscore

def $dollarStartBut the following ones are invalid identifiers:

def 3tier

def a+b

def a#bAll keywords are also valid identifiers when following a dot:

foo.as

foo.assert

foo.break

foo.case

foo.catchQuoted identifiers

Quoted identifiers appear after the dot of a dotted expression.

For instance, the name part of the person.name expression can be quoted with person."name" or person.'name'.

This is particularly interesting when certain identifiers contain illegal characters that are forbidden by the Java Language Specification,

but which are allowed by Groovy when quoted. For example, characters like a dash, a space, an exclamation mark, etc.

def map = [:]

map."an identifier with a space and double quotes" = "ALLOWED"

map.'with-dash-signs-and-single-quotes' = "ALLOWED"

assert map."an identifier with a space and double quotes" == "ALLOWED"

assert map.'with-dash-signs-and-single-quotes' == "ALLOWED"As we shall see in the following section on strings, Groovy provides different string literals. All kind of strings are actually allowed after the dot:

map.'single quote'

map."double quote"

map.'''triple single quote'''

map."""triple double quote"""

map./slashy string/

map.$/dollar slashy string/$There’s a difference between plain character strings and Groovy’s GStrings (interpolated strings), as in that the latter case, the interpolated values are inserted in the final string for evaluating the whole identifier:

def firstname = "Homer"

map."Simson-${firstname}" = "Homer Simson"

assert map.'Simson-Homer' == "Homer Simson"1.1.4. Strings

Text literals are represented in the form of chain of characters called strings.

Groovy lets you instantiate java.lang.String objects, as well as GStrings (groovy.lang.GString)

which are also called interpolated strings in other programming languages.

Single quoted string

Single quoted strings are a series of characters surrounded by single quotes:

'a single quoted string'

Single quoted strings are plain java.lang.String and don’t support interpolation.

|

String concatenation

All the Groovy strings can be concatenated with the + operator:

assert 'ab' == 'a' + 'b'Triple single quoted string

Triple single quoted strings are a series of characters surrounded by triplets of single quotes:

'''a triple single quoted string'''

Triple single quoted strings are plain java.lang.String and don’t support interpolation.

|

Triple single quoted strings are multiline. You can span the content of the string across line boundaries without the need to split the string in several pieces, without contatenation or newline escape characters:

def aMultilineString = '''line one

line two

line three'''If your code is indented, for example in the body of the method of a class, your string will contain the whitespace of the indentation.

The Groovy Development Kit contains methods for stripping out the indentation with the String#stripIndent() method,

and with the String#stripMargin() method that takes a delimiter character to identify the text to remove from the beginning of a string.

When creating a string as follows:

def startingAndEndingWithANewline = '''

line one

line two

line three

'''You will notice that the resulting string contains a newline character as first character. It is possible to strip that character by escaping the newline with a backslash:

def strippedFirstNewline = '''\

line one

line two

line three

'''

assert !strippedFirstNewline.startsWith('\n')Escaping special characters

You can escape single quotes with the the backslash character to avoid terminating the string literal:

'an escaped single quote: \' needs a backslash'And you can escape the escape character itself with a double backslash:

'an escaped escape character: \\ needs a double backslash'Some special characters also use the backslash as escape character:

| Escape sequence | Character |

|---|---|

'\t' |

tabulation |

'\b' |

backspace |

'\n' |

newline |

'\r' |

carriage return |

'\f' |

formfeed |

'\\' |

backslash |

'\'' |

single quote (for single quoted and triple single quoted strings) |

'\"' |

double quote (for double quoted and triple double quoted strings) |

Double quoted string

Double quoted strings are a series of characters surrounded by double quotes:

"a double quoted string"

Double quoted strings are plain java.lang.String if there’s no interpolated expression,

but are groovy.lang.GString instances if interpolation is present.

|

| To escape a double quote, you can use the backslash character: "A double quote: \"". |

String interpolation

Any Groovy expression can be interpolated in all string literals, apart from single and triple single quoted strings.

Interpolation is the act of replacing a placeholder in the string with its value upon evaluation of the string.

The placeholder expressions are surrounded by ${} or prefixed with $ for dotted expressions.

The expression value inside the placeholder is evaluated to its string representation when the GString is passed to a method taking a String as argument by calling toString() on that expression.

Here, we have a string with a placeholder referencing a local variable:

def name = 'Guillaume' // a plain string

def greeting = "Hello ${name}"

assert greeting.toString() == 'Hello Guillaume'But any Groovy expression is valid, as we can see in this example with an arithmetic expression:

def sum = "The sum of 2 and 3 equals ${2 + 3}"

assert sum.toString() == 'The sum of 2 and 3 equals 5'

Not only expressions are actually allowed in between the ${} placeholder. Statements are also allowed, but a statement’s value is just null.

So if several statements are inserted in that placeholder, the last one should somehow return a meaningful value to be inserted.

For instance, "The sum of 1 and 2 is equal to ${def a = 1; def b = 2; a + b}" is supported and works as expected but a good practice is usually to stick to simple expressions inside GString placeholders.

|

In addition to ${} placeholders, we can also use a lone $ sign prefixing a dotted expression:

def person = [name: 'Guillaume', age: 36]

assert "$person.name is $person.age years old" == 'Guillaume is 36 years old'But only dotted expressions of the form a.b, a.b.c, etc, are valid, but expressions that would contain parentheses like method calls, curly braces for closures, or arithmetic operators would be invalid.

Given the following variable definition of a number:

def number = 3.14The following statement will throw a groovy.lang.MissingPropertyException because Groovy believes you’re trying to access the toString property of that number, which doesn’t exist:

shouldFail(MissingPropertyException) {

println "$number.toString()"

}

You can think of "$number.toString()" as being interpreted by the parser as "${number.toString}()".

|

If you need to escape the $ or ${} placeholders in a GString so they appear as is without interpolation,

you just need to use a \ backslash character to escape the dollar sign:

assert '${name}' == "\${name}"Special case of interpolating closure expressions

So far, we’ve seen we could interpolate arbitrary expressions inside the ${} placeholder, but there is a special case and notation for closure expressions. When the placeholder contains an arrow, ${→}, the expression is actually a closure expression — you can think of it as a closure with a dollar prepended in front of it:

def sParameterLessClosure = "1 + 2 == ${-> 3}" (1)

assert sParameterLessClosure == '1 + 2 == 3'

def sOneParamClosure = "1 + 2 == ${ w -> w << 3}" (2)

assert sOneParamClosure == '1 + 2 == 3'| 1 | The closure is a parameterless closure which doesn’t take arguments. |

| 2 | Here, the closure takes a single java.io.StringWriter argument, to which you can append content with the << leftShift operator.

In either case, both placeholders are embedded closures. |

In appearance, it looks like a more verbose way of defining expressions to be interpolated, but closures have an interesting advantage over mere expressions: lazy evaluation.

Let’s consider the following sample:

def number = 1 (1)

def eagerGString = "value == ${number}"

def lazyGString = "value == ${ -> number }"

assert eagerGString == "value == 1" (2)

assert lazyGString == "value == 1" (3)

number = 2 (4)

assert eagerGString == "value == 1" (5)

assert lazyGString == "value == 2" (6)| 1 | We define a number variable containing 1 that we then interpolate within two GStrings,

as an expression in eagerGString and as a closure in lazyGString. |

| 2 | We expect the resulting string to contain the same string value of 1 for eagerGString. |

| 3 | Similarly for lazyGString |

| 4 | Then we change the value of the variable to a new number |

| 5 | With a plain interpolated expression, the value was actually bound at the time of creation of the GString. |

| 6 | But with a closure expression, the closure is called upon each coercion of the GString into String, resulting in an updated string containing the new number value. |

| An embedded closure expression taking more than one parameter will generate an exception at runtime. Only closures with zero or one parameters are allowed. |

Interoperability with Java

When a method (whether implemented in Java or Groovy) expects a java.lang.String,

but we pass a groovy.lang.GString instance,

the toString() method of the GString is automatically and transparently called.

String takeString(String message) { (4)

assert message instanceof String (5)

return message

}

def message = "The message is ${'hello'}" (1)

assert message instanceof GString (2)

def result = takeString(message) (3)

assert result instanceof String

assert result == 'The message is hello'| 1 | We create a GString variable |

| 2 | We double check it’s an instance of the GString |

| 3 | We then pass that GString to a method taking a String as parameter |

| 4 | The signature of the takeString() method explicitly says its sole parameter is a String |

| 5 | We also verify that the parameter is indeed a String and not a GString. |

GString and String hashCodes

Although interpolated strings can be used in lieu of plain Java strings, they differ with strings in a particular way: their hashCodes are different. Plain Java strings are immutable, whereas the resulting String representation of a GString can vary, depending on its interpolated values. Even for the same resulting string, GStrings and Strings don’t have the same hashCode.

assert "one: ${1}".hashCode() != "one: 1".hashCode()GString and Strings having different hashCode values, using GString as Map keys should be avoided, especially if we try to retrieve an associated value with a String instead of a GString.

def key = "a"

def m = ["${key}": "letter ${key}"] (1)

assert m["a"] == null (2)| 1 | The map is created with an initial pair whose key is a GString |

| 2 | When we try to fetch the value with a String key, we will not find it, as Strings and GString have different hashCode values |

Triple double quoted string

Triple double quoted strings behave like double quoted strings, with the addition that they are multiline, like the triple single quoted strings.

def name = 'Groovy'

def template = """

Dear Mr ${name},

You're the winner of the lottery!

Yours sincerly,

Dave

"""

assert template.toString().contains('Groovy')| Neither double quotes nor single quotes need be escaped in triple double quoted strings. |

Slashy string

Beyond the usual quoted strings, Groovy offers slashy strings, which use / as delimiters.

Slashy strings are particularly useful for defining regular expressions and patterns,

as there is no need to escape backslashes.

Example of a slashy string:

def fooPattern = /.*foo.*/

assert fooPattern == '.*foo.*'Only forward slashes need to be escaped with a backslash:

def escapeSlash = /The character \/ is a forward slash/

assert escapeSlash == 'The character / is a forward slash'Slashy strings are multiline:

def multilineSlashy = /one

two

three/

assert multilineSlashy.contains('\n')Slashy strings can also be interpolated (ie. a GString):

def color = 'blue'

def interpolatedSlashy = /a ${color} car/

assert interpolatedSlashy == 'a blue car'There are a few gotchas to be aware of.

An empty slashy string cannot be represented with a double forward slash, as it’s understood by the Groovy parser as a line comment. That’s why the following assert would actually not compile as it would look like a non-terminated statement:

assert '' == //

As slashy strings were mostly designed to make regexp easier so a few things that are errors in GStrings like $() will work with slashy strings.

|

Dollar slashy string

Dollar slashy strings are multiline GStrings delimited with an opening $/ and and a closing /$.

The escaping character is the dollar sign, and it can escape another dollar, or a forward slash.

But both dollar and forward slashes don’t need to be escaped, except to escape the dollar of a string subsequence that would start like a GString placeholder sequence, or if you need to escape a sequence that would start like a closing dollar slashy string delimiter.

Here’s an example:

def name = "Guillaume"

def date = "April, 1st"

def dollarSlashy = $/

Hello $name,

today we're ${date}.

$ dollar sign

$$ escaped dollar sign

\ backslash

/ forward slash

$/ escaped forward slash

$/$ escaped dollar slashy string delimiter

/$

assert [

'Guillaume',

'April, 1st',

'$ dollar sign',

'$ escaped dollar sign',

'\\ backslash',

'/ forward slash',

'$/ escaped forward slash',

'/$ escaped dollar slashy string delimiter'

].each { dollarSlashy.contains(it) }String summary table

String name |

String syntax |

Interpolated |

Multiline |

Escape character |

Single quoted |

|

|

||

Triple single quoted |

|

|

||

Double quoted |

|

|

||

Triple double quoted |

|

|

||

Slashy |

|

|

||

Dollar slashy |

|

|

Characters

Unlike Java, Groovy doesn’t have an explicit character literal. However, you can be explicit about making a Groovy string an actual character, by three different means:

char c1 = 'A' (1)

assert c1 instanceof Character

def c2 = 'B' as char (2)

assert c2 instanceof Character

def c3 = (char)'C' (3)

assert c3 instanceof Character| 1 | by being explicit when declaring a variable holding the character by specifying the char type |

| 2 | by using type coercion with the as operator |

| 3 | by using a cast to char operation |

| The first option 1 is interesting when the character is held in a variable, while the other two (2 and 3) are more interesting when a char value must be passed as argument of a method call. |

1.1.5. Numbers

Groovy supports different kinds of integral literals and decimal literals, backed by the usual Number types of Java.

Integral literals

The integral literal types are the same as in Java:

-

byte -

char -

short -

int -

long -

java.lang.BigInteger

You can create integral numbers of those types with the following declarations:

// primitive types

byte b = 1

char c = 2

short s = 3

int i = 4

long l = 5

// infinite precision

BigInteger bi = 6If you use optional typing by using the def keyword, the type of the integral number will vary:

it’ll adapt to the capacity of the type that can hold that number.

For positive numbers:

def a = 1

assert a instanceof Integer

// Integer.MAX_VALUE

def b = 2147483647

assert b instanceof Integer

// Integer.MAX_VALUE + 1

def c = 2147483648

assert c instanceof Long

// Long.MAX_VALUE

def d = 9223372036854775807

assert d instanceof Long

// Long.MAX_VALUE + 1

def e = 9223372036854775808

assert e instanceof BigIntegerAs well as for negative numbers:

def na = -1

assert na instanceof Integer

// Integer.MIN_VALUE

def nb = -2147483648

assert nb instanceof Integer

// Integer.MIN_VALUE - 1

def nc = -2147483649

assert nc instanceof Long

// Long.MIN_VALUE

def nd = -9223372036854775808

assert nd instanceof Long

// Long.MIN_VALUE - 1

def ne = -9223372036854775809

assert ne instanceof BigIntegerAlternative non-base 10 representations

Numbers can also be represented in binary, octal, hexadecimal and decimal bases.

Binary numbers start with a 0b prefix:

int xInt = 0b10101111

assert xInt == 175

short xShort = 0b11001001

assert xShort == 201 as short

byte xByte = 0b11

assert xByte == 3 as byte

long xLong = 0b101101101101

assert xLong == 2925l

BigInteger xBigInteger = 0b111100100001

assert xBigInteger == 3873g

int xNegativeInt = -0b10101111

assert xNegativeInt == -175Octal numbers are specified in the typical format of 0 followed by octal digits.

int xInt = 077

assert xInt == 63

short xShort = 011

assert xShort == 9 as short

byte xByte = 032

assert xByte == 26 as byte

long xLong = 0246

assert xLong == 166l

BigInteger xBigInteger = 01111

assert xBigInteger == 585g

int xNegativeInt = -077

assert xNegativeInt == -63Hexadecimal numbers are specified in the typical format of 0x followed by hex digits.

int xInt = 0x77

assert xInt == 119

short xShort = 0xaa

assert xShort == 170 as short

byte xByte = 0x3a

assert xByte == 58 as byte

long xLong = 0xffff

assert xLong == 65535l

BigInteger xBigInteger = 0xaaaa

assert xBigInteger == 43690g

Double xDouble = new Double('0x1.0p0')

assert xDouble == 1.0d

int xNegativeInt = -0x77

assert xNegativeInt == -119Decimal literals

The decimal literal types are the same as in Java:

-

float -

double -

java.lang.BigDecimal

You can create decimal numbers of those types with the following declarations:

// primitive types

float f = 1.234

double d = 2.345

// infinite precision

BigDecimal bd = 3.456Decimals can use exponents, with the e or E exponent letter, followed by an optional sign,

and a integral number representing the exponent:

assert 1e3 == 1_000.0

assert 2E4 == 20_000.0

assert 3e+1 == 30.0

assert 4E-2 == 0.04

assert 5e-1 == 0.5Conveniently for exact decimal number calculations, Groovy choses java.lang.BigDecimal as its decimal number type.

In addition, both float and double are supported, but require an explicit type declaration, type coercion or suffix.

Even if BigDecimal is the default for decimal numbers, such literals are accepted in methods or closures taking float or double as parameter types.

| Decimal numbers can’t be represented using a binary, octal or hexadecimal representation. |

Underscore in literals

When writing long literal numbers, it’s harder on the eye to figure out how some numbers are grouped together, for example with groups of thousands, of words, etc. By allowing you to place underscore in number literals, it’s easier to spot those groups:

long creditCardNumber = 1234_5678_9012_3456L

long socialSecurityNumbers = 999_99_9999L

double monetaryAmount = 12_345_132.12

long hexBytes = 0xFF_EC_DE_5E

long hexWords = 0xFFEC_DE5E

long maxLong = 0x7fff_ffff_ffff_ffffL

long alsoMaxLong = 9_223_372_036_854_775_807L

long bytes = 0b11010010_01101001_10010100_10010010Number type suffixes

We can force a number (including binary, octals and hexadecimals) to have a specific type by giving a suffix (see table bellow), either uppercase or lowercase.

| Type | Suffix |

|---|---|

BigInteger |

|

Long |

|

Integer |

|

BigDecimal |

|

Double |

|

Float |

|

Examples:

assert 42I == new Integer('42')

assert 42i == new Integer('42') // lowercase i more readable

assert 123L == new Long("123") // uppercase L more readable

assert 2147483648 == new Long('2147483648') // Long type used, value too large for an Integer

assert 456G == new BigInteger('456')

assert 456g == new BigInteger('456')

assert 123.45 == new BigDecimal('123.45') // default BigDecimal type used

assert 1.200065D == new Double('1.200065')

assert 1.234F == new Float('1.234')

assert 1.23E23D == new Double('1.23E23')

assert 0b1111L.class == Long // binary

assert 0xFFi.class == Integer // hexadecimal

assert 034G.class == BigInteger // octalMath operations

Although operators are covered later on, it’s important to discuss the behavior of math operations and what their resulting types are.

Division and power binary operations aside (covered below),

-

binary operations between

byte,char,shortandintresult inint -

binary operations involving

longwithbyte,char,shortandintresult inlong -

binary operations involving

BigIntegerand any other integral type result inBigInteger -

binary operations involving

BigDecimalwithbyte,char,short,intandBigIntegerresult inBigDecimal -

binary operations between

float,doubleandBigDecimalresult indouble -

binary operations between two

BigDecimalresult inBigDecimal

The following table summarizes those rules:

| byte | char | short | int | long | BigInteger | float | double | BigDecimal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

byte |

int |

int |

int |

int |

long |

BigInteger |

double |

double |

BigDecimal |

char |

int |

int |

int |

long |

BigInteger |

double |

double |

BigDecimal |

|

short |

int |

int |

long |

BigInteger |

double |

double |

BigDecimal |

||

int |

int |

long |

BigInteger |

double |

double |

BigDecimal |

|||

long |

long |

BigInteger |

double |

double |

BigDecimal |

||||

BigInteger |

BigInteger |

double |

double |

BigDecimal |

|||||

float |

double |

double |

double |

||||||

double |

double |

double |

|||||||

BigDecimal |

BigDecimal |

Thanks to Groovy’s operator overloading, the usual arithmetic operators work as well with BigInteger and BigDecimal,

unlike in Java where you have to use explicit methods for operating on those numbers.

|

The case of the division operator

The division operators / (and /= for division and assignment) produce a double result

if either operand is a float or double, and a BigDecimal result otherwise

(when both operands are any combination of an integral type short, char, byte, int, long,

BigInteger or BigDecimal).

BigDecimal division is performed with the divide() method if the division is exact

(i.e. yielding a result that can be represented within the bounds of the same precision and scale),

or using a MathContext with a precision

of the maximum of the two operands' precision plus an extra precision of 10,

and a scale

of the maximum of 10 and the maximum of the operands' scale.

For integer division like in Java, you should use the intdiv() method,

as Groovy doesn’t provide a dedicated integer division operator symbol.

|

The case of the power operator

The power operation is represented by the ** operator, with two parameters: the base and the exponent.

The result of the power operation depends on its operands, and the result of the operation

(in particular if the result can be represented as an integral value).

The following rules are used by Groovy’s power operation to determine the resulting type:

-

If the exponent is a decimal value

-

if the result can be represented as an

Integer, then return anInteger -

else if the result can be represented as a

Long, then return aLong -

otherwise return a

Double

-

-

If the exponent is an integral value

-

if the exponent is strictly negative, then return an

Integer,LongorDoubleif the result value fits in that type -

if the exponent is positive or zero

-

if the base is a

BigDecimal, then return aBigDecimalresult value -

if the base is a

BigInteger, then return aBigIntegerresult value -

if the base is an

Integer, then return anIntegerif the result value fits in it, otherwise aBigInteger -

if the base is a

Long, then return aLongif the result value fits in it, otherwise aBigInteger

-

-

We can illustrate those rules with a few examples:

// base and exponent are ints and the result can be represented by an Integer

assert 2 ** 3 instanceof Integer // 8

assert 10 ** 9 instanceof Integer // 1_000_000_000

// the base is a long, so fit the result in a Long

// (although it could have fit in an Integer)

assert 5L ** 2 instanceof Long // 25

// the result can't be represented as an Integer or Long, so return a BigInteger

assert 100 ** 10 instanceof BigInteger // 10e20

assert 1234 ** 123 instanceof BigInteger // 170515806212727042875...

// the base is a BigDecimal and the exponent a negative int

// but the result can be represented as an Integer

assert 0.5 ** -2 instanceof Integer // 4

// the base is an int, and the exponent a negative float

// but again, the result can be represented as an Integer

assert 1 ** -0.3f instanceof Integer // 1

// the base is an int, and the exponent a negative int

// but the result will be calculated as a Double

// (both base and exponent are actually converted to doubles)

assert 10 ** -1 instanceof Double // 0.1

// the base is a BigDecimal, and the exponent is an int, so return a BigDecimal

assert 1.2 ** 10 instanceof BigDecimal // 6.1917364224

// the base is a float or double, and the exponent is an int

// but the result can only be represented as a Double value

assert 3.4f ** 5 instanceof Double // 454.35430372146965

assert 5.6d ** 2 instanceof Double // 31.359999999999996

// the exponent is a decimal value

// and the result can only be represented as a Double value

assert 7.8 ** 1.9 instanceof Double // 49.542708423868476

assert 2 ** 0.1f instanceof Double // 1.07177346364329561.1.6. Booleans

Boolean is a special data type that is used to represent truth values: true and false.

Use this data type for simple flags that track true/false conditions.

Boolean values can be stored in variables, assigned into fields, just like any other data type:

def myBooleanVariable = true

boolean untypedBooleanVar = false

booleanField = truetrue and false are the only two primitive boolean values.

But more complex boolean expressions can be represented using logical operators.

In addition, Groovy has special rules (often referred to as Groovy Truth) for coercing non-boolean objects to a boolean value.

1.1.7. Lists

Groovy uses a comma-separated list of values, surrounded by square brackets, to denote lists.

Groovy lists are plain JDK java.util.List, as Groovy doesn’t define its own collection classes.

The concrete list implementation used when defining list literals are java.util.ArrayList by default,

unless you decide to specify otherwise, as we shall see later on.

def numbers = [1, 2, 3] (1)

assert numbers instanceof List (2)

assert numbers.size() == 3 (3)| 1 | We define a list numbers delimited by commas and surrounded by square brackets, and we assign that list into a variable |

| 2 | The list is an instance of Java’s java.util.List interface |

| 3 | The size of the list can be queried with the size() method, and shows our list contains 3 elements |

In the above example, we used a homogeneous list, but you can also create lists containing values of heterogeneous types:

def heterogeneous = [1, "a", true] (1)| 1 | Our list here contains a number, a string and a boolean value |

We mentioned that by default, list literals are actually instances of java.util.ArrayList,

but it is possible to use a different backing type for our lists,

thanks to using type coercion with the as operator, or with explicit type declaration for your variables:

def arrayList = [1, 2, 3]

assert arrayList instanceof java.util.ArrayList

def linkedList = [2, 3, 4] as LinkedList (1)

assert linkedList instanceof java.util.LinkedList

LinkedList otherLinked = [3, 4, 5] (2)

assert otherLinked instanceof java.util.LinkedList| 1 | We use coercion with the as operator to explicitly request a java.util.LinkedList implementation |

| 2 | We can say that the variable holding the list literal is of type java.util.LinkedList |

You can access elements of the list with the [] subscript operator (both for reading and setting values)

with positive indices or negative indices to access elements from the end of the list, as well as with ranges,

and use the << leftShift operator to append elements to a list:

def letters = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

assert letters[0] == 'a' (1)

assert letters[1] == 'b'

assert letters[-1] == 'd' (2)

assert letters[-2] == 'c'

letters[2] = 'C' (3)

assert letters[2] == 'C'

letters << 'e' (4)

assert letters[ 4] == 'e'

assert letters[-1] == 'e'

assert letters[1, 3] == ['b', 'd'] (5)

assert letters[2..4] == ['C', 'd', 'e'] (6)| 1 | Access the first element of the list (zero-based counting) |

| 2 | Access the last element of the list with a negative index: -1 is the first element from the end of the list |

| 3 | Use an assignment to set a new value for the third element of the list |

| 4 | Use the << leftShift operator to append an element at the end of the list |

| 5 | Access two elements at once, returning a new list containing those two elements |

| 6 | Use a range to access a range of values from the list, from a start to an end element position |

As lists can be heterogeneous in nature, lists can also contain other lists to create multi-dimensional lists:

def multi = [[0, 1], [2, 3]] (1)

assert multi[1][0] == 2 (2)| 1 | Define a list of list of numbers |

| 2 | Access the second element of the top-most list, and the first element of the inner list |

1.1.8. Arrays

Groovy reuses the list notation for arrays, but to make such literals arrays, you need to explicitely define the type of the array through coercion or type declaration.

String[] arrStr = ['Ananas', 'Banana', 'Kiwi'] (1)

assert arrStr instanceof String[] (2)

assert !(arrStr instanceof List)

def numArr = [1, 2, 3] as int[] (3)

assert numArr instanceof int[] (4)

assert numArr.size() == 3| 1 | Define an array of strings using explicit variable type declaration |

| 2 | Assert that we created an array of strings |

| 3 | Create an array of ints with the as operator |

| 4 | Assert that we created an array of primitive ints |

You can also create multi-dimensional arrays:

def matrix3 = new Integer[3][3] (1)

assert matrix3.size() == 3

Integer[][] matrix2 (2)

matrix2 = [[1, 2], [3, 4]]

assert matrix2 instanceof Integer[][]| 1 | You can define the bounds of a new array |

| 2 | Or declare an array without specifying its bounds |

Access to elements of an array follows the same notation as for lists:

String[] names = ['Cédric', 'Guillaume', 'Jochen', 'Paul']

assert names[0] == 'Cédric' (1)

names[2] = 'Blackdrag' (2)

assert names[2] == 'Blackdrag'| 1 | Retrieve the first element of the array |

| 2 | Set the value of the third element of the array to a new value |

| Java’s array initializer notation is not supported by Groovy, as the curly braces can be misinterpreted with the notation of Groovy closures. |

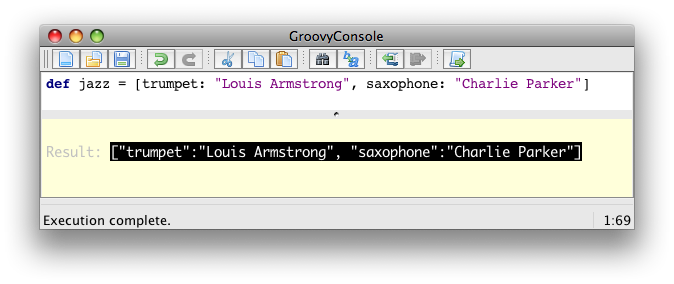

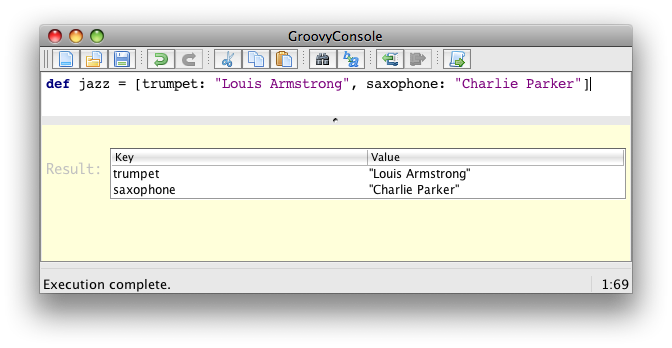

1.1.9. Maps

Sometimes called dictionaries or associative arrays in other languages, Groovy features maps. Maps associate keys to values, separating keys and values with colons, and each key/value pairs with commas, and the whole keys and values surrounded by square brackets.

def colors = [red: '#FF0000', green: '#00FF00', blue: '#0000FF'] (1)

assert colors['red'] == '#FF0000' (2)

assert colors.green == '#00FF00' (3)

colors['pink'] = '#FF00FF' (4)

colors.yellow = '#FFFF00' (5)

assert colors.pink == '#FF00FF'

assert colors['yellow'] == '#FFFF00'

assert colors instanceof java.util.LinkedHashMap| 1 | We define a map of string color names, associated with their hexadecimal-coded html colors |

| 2 | We use the subscript notation to check the content associated with the red key |

| 3 | We can also use the property notation to assert the color green’s hexadecimal representation |

| 4 | Similarly, we can use the subscript notation to add a new key/value pair |

| 5 | Or the property notation, to add the yellow color |

| When using names for the keys, we actually define string keys in the map. |

Groovy creates maps that are actually instances of java.util.LinkedHashMap.

|

If you try to access a key which is not present in the map:

assert colors.unknown == nullYou will retrieve a null result.

In the examples above, we used string keys, but you can also use values of other types as keys:

def numbers = [1: 'one', 2: 'two']

assert numbers[1] == 'one'Here, we used numbers as keys, as numbers can unambiguously be recognized as numbers, so Groovy will not create a string key like in our previous examples. But consider the case you want to pass a variable in lieu of the key, to have the value of that variable become the key:

def key = 'name'

def person = [key: 'Guillaume'] (1)

assert !person.containsKey('name') (2)

assert person.containsKey('key') (3)| 1 | The key associated with the 'Guillaume' name will actually be the "key" string, not the value associated with the key variable |

| 2 | The map doesn’t contain the 'name' key |

| 3 | Instead, the map contains a 'key' key |

| You can also pass quoted strings as well as keys: ["name": "Guillaume"]. This is mandatory if your key string isn’t a valid identifier, for example if you wanted to create a string key containing a hash like in: ["street-name": "Main street"]. |

When you need to pass variable values as keys in your map definitions, you must surround the variable or expression with parentheses:

person = [(key): 'Guillaume'] (1)

assert person.containsKey('name') (2)

assert !person.containsKey('key') (3)| 1 | This time, we surround the key variable with parentheses, to instruct the parser we are passing a variable rather than defining a string key |

| 2 | The map does contain the name key |

| 3 | But the map doesn’t contain the key key as before |

1.2. Operators

This chapter covers the operators of the Groovy programming language.

1.2.1. Arithmetic operators

Groovy supports the usual familiar arithmetic operators you find in mathematics and in other programming languages like Java. All the Java arithmetic operators are supported. Let’s go through them in the following examples.

Normal arithmetic operators

The following binary arithmetic operators are available in Groovy:

| Operator | Purpose | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

|

addition |

|

|

subtraction |

|

|

multiplication |

|

|

division |

Use |

|

remainder |

|

|

power |

See the section about the power operation for more information on the return type of the operation. |

Here are a few examples of usage of those operators:

assert 1 + 2 == 3

assert 4 - 3 == 1

assert 3 * 5 == 15

assert 3 / 2 == 1.5

assert 10 % 3 == 1

assert 2 ** 3 == 8Unary operators

The + and - operators are also available as unary operators:

assert +3 == 3

assert -4 == 0 - 4

assert -(-1) == 1 (1)| 1 | Note the usage of parentheses to surround an expression to apply the unary minus to that surrounded expression. |

In terms of unary arithmetics operators, the ++ (increment) and -- (decrement) operators are available,

both in prefix and postfix notation:

def a = 2

def b = a++ * 3 (1)

assert a == 3 && b == 6

def c = 3

def d = c-- * 2 (2)

assert c == 2 && d == 6

def e = 1

def f = ++e + 3 (3)

assert e == 2 && f == 5

def g = 4

def h = --g + 1 (4)

assert g == 3 && h == 4| 1 | The postfix increment will increment a after the expression has been evaluated and assigned into b |

| 2 | The postfix decrement will decrement c after the expression has been evaluated and assigned into d |

| 3 | The prefix increment will increment e before the expression is evaluated and assigned into f |

| 4 | The prefix decrement will decrement g before the expression is evaluated and assigned into h |

Assignment arithmetic operators

The binary arithmetic operators we have seen above are also available in an assignment form:

-

+= -

-= -

*= -

/= -

%= -

**=

Let’s see them in action:

def a = 4

a += 3

assert a == 7

def b = 5

b -= 3

assert b == 2

def c = 5

c *= 3

assert c == 15

def d = 10

d /= 2

assert d == 5

def e = 10

e %= 3

assert e == 1

def f = 3

f **= 2

assert f == 91.2.2. Relational operators

Relational operators allow comparisons between objects, to know if two objects are the same or different, or if one is greater than, less than, or equal to the other.

The following operators are available:

| Operator | Purpose |

|---|---|

|

equal |

|

different |

|

less than |

|

less than or equal |

|

greater than |

|

greater than or equal |

Here are some examples of simple number comparisons using these operators:

assert 1 + 2 == 3

assert 3 != 4

assert -2 < 3

assert 2 <= 2

assert 3 <= 4

assert 5 > 1

assert 5 >= -21.2.3. Logical operators

Groovy offers three logical operators for boolean expressions:

-

&&: logical "and" -

||: logical "or" -

!: logical "not"

Let’s illustrate them with the following examples:

assert !false (1)

assert true && true (2)

assert true || false (3)| 1 | "not" false is true |

| 2 | true "and" true is true |

| 3 | true "or" false is true |

Precedence

The logical "not" has a higher priority than the logical "and".

assert (!false && false) == false (1)| 1 | Here, the assertion is true (as the expression in parentheses is false), because "not" has a higher precedence than "and", so it only applies to the first "false" term; otherwise, it would have applied to the result of the "and", turned it into true, and the assertion would have failed |

The logical "and" has a higher priority than the logical "or".

assert true || true && false (1)| 1 | Here, the assertion is true, because "and" has a higher precedence than "or", therefore the "or" is executed last and returns true, having one true argument; otherwise, the "and" would have executed last and returned false, having one false argument, and the assertion would have failed |

Short-circuiting

The logical || operator supports short-circuiting: if the left operand is true, it knows that the result will be true in any case, so it won’t evaluate the right operand.

The right operand will be evaluated only if the left operand is false.

Likewise for the logical && operator: if the left operand is false, it knows that the result will be false in any case, so it won’t evaluate the right operand.

The right operand will be evaluated only if the left operand is true.

boolean checkIfCalled() { (1)

called = true

}

called = false

true || checkIfCalled()

assert !called (2)

called = false

false || checkIfCalled()

assert called (3)

called = false

false && checkIfCalled()

assert !called (4)

called = false

true && checkIfCalled()

assert called (5)| 1 | We create a function that sets the called flag to true whenever it’s called |

| 2 | In the first case, after resetting the called flag, we confirm that if the left operand to || is true, the function is not called, as || short-circuits the evaluation of the right operand |

| 3 | In the second case, the left operand is false and so the function is called, as indicated by the fact our flag is now true |

| 4 | Likewise for &&, we confirm that the function is not called with a false left operand |

| 5 | But the function is called with a true left operand |

1.2.4. Bitwise operators

Groovy offers 4 bitwise operators:

-

&: bitwise "and" -

|: bitwise "or" -

^: bitwise "xor" (exclusive "or") -

~: bitwise negation

Bitwise operators can be applied on a byte or an int and return an int:

int a = 0b00101010

assert a==42

int b = 0b00001000

assert b==8

assert (a & a) == a (1)

assert (a & b) == b (2)

assert (a | a) == a (3)

assert (a | b) == a (4)

int mask = 0b11111111 (5)

assert ((a ^ a) & mask) == 0b00000000 (6)

assert ((a ^ b) & mask) == 0b00100010 (7)

assert ((~a) & mask) == 0b11010101 (8)| 1 | bitwise and |

| 2 | bitwise and returns common bits |

| 3 | bitwise or |

| 4 | bitwise or returns all '1' bits |

| 5 | setting a mask to check only the last 8 bits |

| 6 | bitwise exclusive or on self returns 0 |

| 7 | bitwise exclusive or |

| 8 | bitwise negation |

It’s worth noting that the internal representation of primitive types follow the Java Language Specification. In particular, primitive types are signed, meaning that for a bitwise negation, it is always good to use a mask to retrieve only the necessary bits.

In Groovy, bitwise operators have the particularity of being overloadable, meaning that you can define the behavior of those operators for any kind of object.

1.2.5. Conditional operators

Not operator

The "not" operator is represented with an exclamation mark (!) and inverts the result of the underlying boolean expression. In

particular, it is possible to combine the not operator with the Groovy truth:

assert (!true) == false (1)

assert (!'foo') == false (2)

assert (!'') == true (3)| 1 | the negation of true is false |

| 2 | 'foo' is a non empty string, evaluating to true, so negation returns false |

| 3 | '' is an empty string, evaluating to false, so negation returns true |

Ternary operator

The ternary operator is a shortcut expression that is equivalent to an if/else branch assigning some value to a variable.

Instead of:

if (string!=null && string.length()>0) {

result = 'Found'

} else {

result = 'Not found'

}You can write:

result = (string!=null && string.length()>0) ? 'Found' : 'Not found'The ternary operator is also compatible with the Groovy truth, so you can make it even simpler:

result = string ? 'Found' : 'Not found'Elvis operator

The "Elvis operator" is a shortening of the ternary operator. One instance of where this is handy is for returning

a 'sensible default' value if an expression resolves to false-ish (as in

Groovy truth). A simple example might look like this:

displayName = user.name ? user.name : 'Anonymous' (1)

displayName = user.name ?: 'Anonymous' (2)| 1 | with the ternary operator, you have to repeat the value you want to assign |

| 2 | with the Elvis operator, the value, which is tested, is used if it is not false-ish |

Usage of the Elvis operator reduces the verbosity of your code and reduces the risks of errors in case of refactorings, by removing the need to duplicate the expression which is tested in both the condition and the positive return value.

1.2.6. Object operators

Safe navigation operator

The Safe Navigation operator is used to avoid a NullPointerException. Typically when you have a reference to an object

you might need to verify that it is not null before accessing methods or properties of the object. To avoid this, the safe

navigation operator will simply return null instead of throwing an exception, like so:

def person = Person.find { it.id == 123 } (1)

def name = person?.name (2)

assert name == null (3)| 1 | find will return a null instance |

| 2 | use of the null-safe operator prevents from a NullPointerException |

| 3 | result is null |

Direct field access operator

Normally in Groovy, when you write code like this:

class User {

public final String name (1)

User(String name) { this.name = name}

String getName() { "Name: $name" } (2)

}

def user = new User('Bob')

assert user.name == 'Name: Bob' (3)| 1 | public field name |

| 2 | a getter for name that returns a custom string |

| 3 | calls the getter |

The user.name call triggers a call to the property of the same name, that is to say, here, to the getter for name. If

you want to retrieve the field instead of calling the getter, you can use the direct field access operator:

assert user.@name == 'Bob' (1)| 1 | use of .@ forces usage of the field instead of the getter |

Method pointer operator

The method pointer operator (.&) call be used to store a reference to a method in a variable, in order to call it

later:

def str = 'example of method reference' (1)

def fun = str.&toUpperCase (2)

def upper = fun() (3)

assert upper == str.toUpperCase() (4)| 1 | the str variable contains a String |

| 2 | we store a reference to the toUpperCase method on the str instance inside a variable named fun |

| 3 | fun can be called like a regular method |

| 4 | we can check that the result is the same as if we had called it directly on str |

There are multiple advantages in using method pointers. First of all, the type of such a method pointer is

a groovy.lang.Closure, so it can be used in any place a closure would be used. In particular, it is suitable to

convert an existing method for the needs of the strategy pattern:

def transform(List elements, Closure action) { (1)

def result = []

elements.each {

result << action(it)

}

result

}

String describe(Person p) { (2)

"$p.name is $p.age"

}

def action = this.&describe (3)

def list = [

new Person(name: 'Bob', age: 42),

new Person(name: 'Julia', age: 35)] (4)

assert transform(list, action) == ['Bob is 42', 'Julia is 35'] (5)| 1 | the transform method takes each element of the list and calls the action closure on them, returning a new list |

| 2 | we define a function that takes a Person and returns a String |

| 3 | we create a method pointer on that function |

| 4 | we create the list of elements we want to collect the descriptors |

| 5 | the method pointer can be used where a Closure was expected |

Method pointers are bound by the receiver and a method name. Arguments are resolved at runtime, meaning that if you have multiple methods with the same name, the syntax is not different, only resolution of the appropriate method to be called will be done at runtime:

def doSomething(String str) { str.toUpperCase() } (1)

def doSomething(Integer x) { 2*x } (2)

def reference = this.&doSomething (3)

assert reference('foo') == 'FOO' (4)

assert reference(123) == 246 (5)| 1 | define an overloaded doSomething method accepting a String as an argument |

| 2 | define an overloaded doSomething method accepting an Integer as an argument |

| 3 | create a single method pointer on doSomething, without specifying argument types |

| 4 | using the method pointer with a String calls the String version of doSomething |

| 5 | using the method pointer with an Integer calls the Integer version of doSomething |

1.2.7. Regular expression operators

Pattern operator

The pattern operator (~) provides a simple way to create a java.util.regex.Pattern instance:

def p = ~/foo/

assert p instanceof Patternwhile in general, you find the pattern operator with an expression in a slashy-string, it can be used with any kind of

String in Groovy:

p = ~'foo' (1)

p = ~"foo" (2)

p = ~$/dollar/slashy $ string/$ (3)

p = ~"${pattern}" (4)| 1 | using single quote strings |

| 2 | using double quotes strings |

| 3 | the dollar-slashy string lets you use slashes and the dollar sign without having to escape them |

| 4 | you can also use a GString! |

Find operator

Alternatively to building a pattern, you can directly use the find operator =~ to build a java.util.regex.Matcher

instance:

def text = "some text to match"

def m = text =~ /match/ (1)

assert m instanceof Matcher (2)

if (!m) { (3)

throw new RuntimeException("Oops, text not found!")

}| 1 | =~ creates a matcher against the text variable, using the pattern on the right hand side |

| 2 | the return type of =~ is a Matcher |

| 3 | equivalent to calling if (!m.find()) |

Since a Matcher coerces to a boolean by calling its find method, the =~ operator is consistent with the simple

use of Perl’s =~ operator, when it appears as a predicate (in if, while, etc.).

Match operator

The match operator (==~) is a slight variation of the find operator, that does not return a Matcher but a boolean

and requires a strict match of the input string:

m = text ==~ /match/ (1)

assert m instanceof Boolean (2)

if (m) { (3)

throw new RuntimeException("Should not reach that point!")

}| 1 | ==~ matches the subject with the regular expression, but match must be strict |

| 2 | the return type of ==~ is therefore a boolean |

| 3 | equivalent to calling if (text ==~ /match/) |

1.2.8. Other operators

Spread operator

The Spread Operator (*.) is used to invoke an action on all items of an aggregate object. It is equivalent to calling the action on each item

and collecting the result into a list:

class Car {

String make

String model

}

def cars = [

new Car(make: 'Peugeot', model: '508'),

new Car(make: 'Renault', model: 'Clio')] (1)

def makes = cars*.make (2)

assert makes == ['Peugeot', 'Renault'] (3)| 1 | build a list of Car items. The list is an aggregate of objects. |

| 2 | call the spread operator on the list, accessing the make property of each item |

| 3 | returns a list of strings corresponding to the collection of make items |

The spread operator is null-safe, meaning that if an element of the collection is null, it will return null instead of throwing a NullPointerException:

cars = [

new Car(make: 'Peugeot', model: '508'),

null, (1)

new Car(make: 'Renault', model: 'Clio')]

assert cars*.make == ['Peugeot', null, 'Renault'] (2)

assert null*.make == null (3)| 1 | build a list for which of of the elements is null |

| 2 | using the spread operator will not throw a NullPointerException |

| 3 | the receiver might also be null, in which case the return value is null |

The spread operator can be used on any class which implements the Iterable interface:

class Component {

Long id

String name

}

class CompositeObject implements Iterable<Component> {

def components = [

new Component(id: 1, name: 'Foo'),

new Component(id: 2, name: 'Bar')]

@Override

Iterator<Component> iterator() {

components.iterator()

}

}

def composite = new CompositeObject()

assert composite*.id == [1,2]

assert composite*.name == ['Foo','Bar']Spreading method arguments

There may be situations when the arguments of a method call can be found in a list that you need to adapt to the method arguments. In such situations, you can use the spread operator to call the method. For example, imagine you have the following method signature:

int function(int x, int y, int z) {

x*y+z

}then if you have the following list:

def args = [4,5,6]you can call the method without having to define intermediate variables:

assert function(*args) == 26It is even possible to mix normal arguments with spread ones:

args = [4]

assert function(*args,5,6) == 26Spread list elements

When used inside a list literal, the spread operator acts as if the spread element contents were inlined into the list:

def items = [4,5] (1)

def list = [1,2,3,*items,6] (2)

assert list == [1,2,3,4,5,6] (3)| 1 | items is a list |

| 2 | we want to insert the contents of the items list directly into list without having to call addAll |

| 3 | the contents of items has been inlined into list |

Spread map elements

The spread map operator works in a similar manner as the spread list operator, but for maps. It allows you to inline the contents of a map into another map literal, like in the following example:

def m1 = [c:3, d:4] (1)

def map = [a:1, b:2, *:m1] (2)

assert map == [a:1, b:2, c:3, d:4] (3)| 1 | m1 is the map that we want to inline |

| 2 | we use the *:m1 notation to spread the contents of m1 into map |

| 3 | map contains all the elements of m1 |

The position of the spread map operator is relevant, like illustrated in the following example:

def m1 = [c:3, d:4] (1)

def map = [a:1, b:2, *:m1, d: 8] (2)

assert map == [a:1, b:2, c:3, d:8] (3)| 1 | m1 is the map that we want to inline |

| 2 | we use the :m1 notation to spread the contents of m1 into map, but redefine the key d *after spreading |

| 3 | map contains all the expected keys, but d was redefined |

Range operator

Groovy supports the concept of ranges and provides a notation (..) to create ranges of objects:

def range = 0..5 (1)

assert (0..5).collect() == [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] (2)

assert (0..<5).collect() == [0, 1, 2, 3, 4] (3)

assert (0..5) instanceof List (4)

assert (0..5).size() == 6 (5)| 1 | a simple range of integers, stored into a local variable |

| 2 | an IntRange, with inclusive bounds |

| 3 | an IntRange, with exclusive upper bound |

| 4 | a groovy.lang.Range implements the List interface |

| 5 | meaning that you can call the size method on it |

Ranges implementation is lightweight, meaning that only the lower and upper bounds are stored. You can create a range

from any Comparable object that has next() and previous() methods to determine the next / previous item in the range.

For example, you can create a range of characters this way:

assert ('a'..'d').collect() == ['a','b','c','d']Spaceship operator

The spaceship operator (<=>) delegates to the compareTo method:

assert (1 <=> 1) == 0

assert (1 <=> 2) == -1

assert (2 <=> 1) == 1

assert ('a' <=> 'z') == -1Subscript operator

The subscript operator is a short hand notation for getAt or putAt, depending on whether you find it on

the left hand side or the right hand side of an assignment:

def list = [0,1,2,3,4]

assert list[2] == 2 (1)

list[2] = 4 (2)

assert list[0..2] == [0,1,4] (3)

list[0..2] = [6,6,6] (4)

assert list == [6,6,6,3,4] (5)| 1 | [2] can be used instead of getAt(2) |

| 2 | if on left hand side of an assignment, will call putAt |

| 3 | getAt also supports ranges |

| 4 | so does putAt |

| 5 | the list is mutated |

The subscript operator, in combination with a custom implementation of getAt/putAt is a convenient way for destructuring

objects:

class User {

Long id

String name

def getAt(int i) { (1)

switch (i) {

case 0: return id

case 1: return name

}

throw new IllegalArgumentException("No such element $i")

}

void putAt(int i, def value) { (2)

switch (i) {

case 0: id = value; return

case 1: name = value; return

}

throw new IllegalArgumentException("No such element $i")

}

}

def user = new User(id: 1, name: 'Alex') (3)

assert user[0] == 1 (4)

assert user[1] == 'Alex' (5)

user[1] = 'Bob' (6)

assert user.name == 'Bob' (7)| 1 | the User class defines a custom getAt implementation |

| 2 | the User class defines a custom putAt implementation |

| 3 | create a sample user |

| 4 | using the subscript operator with index 0 allows retrieving the user id |

| 5 | using the subscript operator with index 1 allows retrieving the user name |

| 6 | we can use the subscript operator to write to a property thanks to the delegation to putAt |

| 7 | and check that it’s really the property name which was changed |

Membership operator

The membership operator (in) is equivalent to calling the isCase method. In the context of a List, it is equivalent

to calling contains, like in the following example:

def list = ['Grace','Rob','Emmy']

assert ('Emmy' in list) (1)| 1 | equivalent to calling list.contains('Emmy') or list.isCase('Emmy') |

Identity operator

In Groovy, using == to test equality is different from using the same operator in Java. In Groovy, it is calling equals.

If you want to compare reference equality, you should use is like in the following example:

def list1 = ['Groovy 1.8','Groovy 2.0','Groovy 2.3'] (1)

def list2 = ['Groovy 1.8','Groovy 2.0','Groovy 2.3'] (2)

assert list1 == list2 (3)

assert !list1.is(list2) (4)| 1 | Create a list of strings |

| 2 | Create another list of strings containing the same elements |

| 3 | using ==, we test object equality |

| 4 | but using is, we can check that references are distinct |

Coercion operator

The coercion operator (as) is a variant of casting. Coercion converts object from one type to another without them

being compatible for assignment. Let’s take an example:

Integer x = 123

String s = (String) x (1)| 1 | Integer is not assignable to a String, so it will produce a ClassCastException at runtime |

This can be fixed by using coercion instead:

Integer x = 123

String s = x as String (1)| 1 | Integer is not assignable to a String, but use of as will coerce it to a String |

When an object is coerced into another, unless the target type is the same as the source type, coercion will return a

new object. The rules of coercion differ depending on the source and target types, and coercion may fail if no conversion

rules are found. Custom conversion rules may be implemented thanks to the asType method:

class Identifiable {

String name

}

class User {

Long id

String name

def asType(Class target) { (1)

if (target==Identifiable) {

return new Identifiable(name: name)

}

throw new ClassCastException("User cannot be coerced into $target")

}

}

def u = new User(name: 'Xavier') (2)

def p = u as Identifiable (3)

assert p instanceof Identifiable (4)

assert !(p instanceof User) (5)| 1 | the User class defines a custom conversion rule from User to Identifiable |

| 2 | we create an instance of User |

| 3 | we coerce the User instance into an Identifiable |

| 4 | the target is an instance of Identifiable |

| 5 | the target is not an instance of User anymore |

Diamond operator

The diamond operator (<>) is a syntactic sugar only operator added to support compatibility with the operator of the

same name in Java 7. It is used to indicate that generic types should be inferred from the declaration:

List<String> strings = new LinkedList<>()In dynamic Groovy, this is totally unused. In statically type checked Groovy, it is also optional since the Groovy type checker performs type inference whether this operator is present or not.

Call operator

The call operator () is used to call a method named call implicitly. For any object which defines a call method,

you can omit the .call part and use the call operator instead:

class MyCallable {

int call(int x) { (1)

2*x

}

}

def mc = new MyCallable()

assert mc.call(2) == 4 (2)

assert mc(2) == 4 (3)| 1 | MyCallable defines a method named call. Note that it doesn’t need to implement java.util.concurrent.Callable |

| 2 | we can call the method using the classic method call syntax |

| 3 | or we can omit .call thanks to the call operator |

1.2.9. Operator precedence

The table below lists all groovy operators in order of precedence.

| Level | Operator(s) | Name(s) |

|---|---|---|

1 |

|

object creation, explicit parentheses |

|

method call, closure, literal list/map |

|

|

member access, method closure, field/attribute access |

|

|

safe dereferencing, spread, spread-dot, spread-map |

|

|

bitwise negate/pattern, not, typecast |

|

|

list/map/array index, post inc/decrement |

|

2 |

|

power |

3 |

|

pre inc/decrement, unary plus, unary minus |

4 |

|

multiply, div, remainder |

5 |

|

addition, subtraction |

6 |

|

left/right (unsigned) shift, inclusive/exclusive range |

7 |

|

less/greater than/or equal, in, instanceof, type coercion |

8 |

|

equals, not equals, compare to |

|

regex find, regex match |

|

9 |

|

binary/bitwise and |

10 |

|

binary/bitwise xor |

11 |

|

binary/bitwise or |

12 |

|

logical and |

13 |

|

logical or |

14 |

|

ternary conditional |

|

elvis operator |

|

15 |

|

various assignments |

1.2.10. Operator overloading

Groovy allows you to overload the various operators so that they can be used with your own classes. Consider this simple class:

class Bucket {

int size

Bucket(int size) { this.size = size }

Bucket plus(Bucket other) { (1)

return new Bucket(this.size + other.size)

}

}| 1 | Bucket implements a special method called plus() |

Just by implementing the plus() method, the Bucket class can now be used with the + operator like so:

def b1 = new Bucket(4)

def b2 = new Bucket(11)

assert (b1 + b2).size == 15 (1)| 1 | The two Bucket objects can be added together with the + operator |

All (non-comparator) Groovy operators have a corresponding method that you can implement in your own classes. The only requirements are that your method is public, has the correct name, and has the correct number of arguments. The argument types depend on what types you want to support on the right hand side of the operator. For example, you could support the statement

assert (b1 + 11).size == 15by implementing the plus() method with this signature:

Bucket plus(int capacity) {

return new Bucket(this.size + capacity)

}Here is a complete list of the operators and their corresponding methods:

| Operator | Method | Operator | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

|

a.plus(b) |

|

a.getAt(b) |

|

a.minus(b) |

|

a.putAt(b, c) |

|

a.multiply(b) |

|

b.isCase(a) |

|

a.div(b) |

|

a.leftShift(b) |

|

a.mod(b) |

|

a.rightShift(b) |

|

a.power(b) |

|

a.rightShiftUnsigned(b) |

|

a.or(b) |

|

a.next() |

|

a.and(b) |

|

a.previous() |

|

a.xor(b) |

|

a.positive() |

|

a.asType(b) |

|

a.negative() |

|

a.call() |

|

a.bitwiseNegate() |

1.3. Program structure

This chapter covers the program structure of the Groovy programming language.

1.3.1. Package names

Package names play exactly the same role as in Java. They allows us to separate the code base without any conflicts. Groovy classes must specify their package before the class definition, else the default package is assumed.

Defining a package is very similar to Java:

// defining a package named com.yoursite

package com.yoursiteTo refer to some class Foo in the com.yoursite.com package you will need to use the fully qualified name com.yoursite.com.Foo, or else you can use an import statement as we’ll see below.

1.3.2. Imports

In order to refer to any class you need a qualified reference to its package. Groovy follows Java’s notion of allowing import statement to resolve class references.

For example, Groovy provides several builder classes, such as MarkupBuilder. MarkupBuilder is inside the package groovy.xml so in order to use this class, you need to import it as shown:

// importing the class MarkupBuilder

import groovy.xml.MarkupBuilder

// using the imported class to create an object

def xml = new MarkupBuilder()

assert xml != nullDefault imports

Default imports are the imports that Groovy language provides by default. For example look at the following code:

new Date()The same code in Java needs an import statement to Date class like this: import java.util.Date. Groovy by default imports these classes for you.

The below imports are added by groovy for you:

import java.lang.*

import java.util.*

import java.io.*

import java.net.*

import groovy.lang.*

import groovy.util.*

import java.math.BigInteger

import java.math.BigDecimalThis is done because the classes from these packages are most commonly used. By importing these boilerplate code is reduced.

Simple import

A simple import is an import statement where you fully define the class name along with the package. For example the import statement import groovy.xml.MarkupBuilder in the code below is a simple import which directly refers to a class inside a package.

// importing the class MarkupBuilder

import groovy.xml.MarkupBuilder

// using the imported class to create an object

def xml = new MarkupBuilder()

assert xml != nullStar import

Groovy, like Java, provides a special way to import all classes from a package using *, the so called star import. MarkupBuilder is a class which is in package groovy.xml, alongside another class called StreamingMarkupBuilder. In case you need to use both classes, you can do:

import groovy.xml.MarkupBuilder

import groovy.xml.StreamingMarkupBuilder

def markupBuilder = new MarkupBuilder()

assert markupBuilder != null

assert new StreamingMarkupBuilder() != nullThat’s perfectly valid code. But with a * import, we can achieve the same effect with just one line. The star imports all the classes under package groovy.xml:

import groovy.xml.*

def markupBuilder = new MarkupBuilder()

assert markupBuilder != null

assert new StreamingMarkupBuilder() != nullOne problem with * imports is that they can clutter your local namespace. But with the kinds of aliasing provided by Groovy, this can be solved easily.

Static import

Groovy’s static import capability allows you to reference imported classes as if they were static methods in your own class:

import static Boolean.FALSE

assert !FALSE //use directly, without Boolean prefix!This is similar to Java’s static import capability but is a more dynamic than Java in that it allows you to define methods with the same name as an imported method as long as you have different types:

import static java.lang.String.format (1)

class SomeClass {

String format(Integer i) { (2)

i.toString()

}

static void main(String[] args) {

assert format('String') == 'String' (3)

assert new SomeClass().format(Integer.valueOf(1)) == '1'

}

}| 1 | static import of method |

| 2 | declaration of method with same name as method statically imported above, but with a different parameter type |

| 3 | compile error in java, but is valid groovy code |

If you have the same types, the imported class takes precedence.

Static import aliasing

Static imports with the as keyword provide an elegant solution to namespace problems. Suppose you want to get a Calendar instance, using its getInstance() method. It’s a static method, so we can use a static import. But instead of calling getInstance() every time, which can be misleading when separated from its class name, we can import it with an alias, to increase code readability:

import static Calendar.getInstance as now

assert now().class == Calendar.getInstance().classNow, that’s clean!

Static star import

A static star import is very similar to the regular star import. It will import all the static methods from the given class.

For example, lets say we need to calculate sines and cosines for our application.

The class java.lang.Math has static methods named sin and cos which fit our need. With the help of a static star import, we can do:

import static java.lang.Math.*

assert sin(0) == 0.0

assert cos(0) == 1.0As you can see, we were able to access the methods sin and cos directly, without the Math. prefix.

Import aliasing

With type aliasing, we can refer to a fully qualified class name using a name of our choice. This can be done with the as keyword, as before.

For example we can import java.sql.Date as SQLDate and use it in the same file as java.util.Date without having to use the fully qualified name of either class:

import java.util.Date

import java.sql.Date as SQLDate

Date utilDate = new Date(1000L)

SQLDate sqlDate = new SQLDate(1000L)

assert utilDate instanceof java.util.Date

assert sqlDate instanceof java.sql.Date1.3.3. Scripts versus classes

public static void main vs script

Groovy supports both scripts and classes. Take the following code for example:

class Main { (1)

static void main(String... args) { (2)

println 'Groovy world!' (3)

}

}| 1 | define a Main class, the name is arbitrary |

| 2 | the public static void main(String[]) method is usable as the main method of the class |

| 3 | the main body of the method |

This is typical code that you would find coming from Java, where code has to be embedded into a class to be executable. Groovy makes it easier, the following code is equivalent:

println 'Groovy world!'A script can be considered as a class without needing to declare it, with some differences.

Script class

A script is always compiled into a class. The Groovy compiler will compile the class for you,

with the body of the script copied into a run method. The previous example is therefore compiled as if it was the

following:

import org.codehaus.groovy.runtime.InvokerHelper

class Main extends Script { (1)

def run() { (2)

println 'Groovy world!' (3)

}

static void main(String[] args) { (4)

InvokerHelper.runScript(Main, args) (5)

}

}| 1 | The Main class extends the groovy.lang.Script class |

| 2 | groovy.lang.Script requires a run method returning a value |

| 3 | the script body goes into the run method |

| 4 | the main method is automatically generated |